Understanding The Psychology Behind Financial Decisions

How does the stock market work? When’s the best time to buy or dump assets? And how much do you need to save every year to retire by a certain age?

These are the kinds of questions that dominate discussions of personal finance. There’s often something important left out of the equation, however. This is the human factor – in other words, the relationship between real people and their money.

If you want to know why people bury themselves in debt or squander fortunes, you don’t need to study interest rates – you need to delve into the all-too-human history of envy, greed, and optimism.

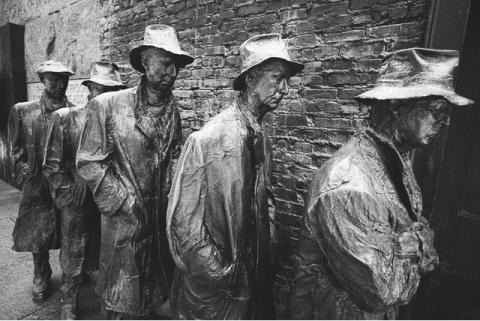

The story of the Great Depression is well-known.

After a disastrous stock market crash in 1929, the global economy entered a decade of sustained decline.

In the United States, the roaring twenties came to an abrupt halt. Businesses folded, families lost their farms and homes, and hard-earned savings disappeared into thin air. Poverty and joblessness skyrocketed, while faith that tomorrow would be better than yesterday plummeted.

Today, this version of events has become the standard narrative. That stands to reason – it does, after all, describe the experience of millions of Americans. But it also leaves something important out of the picture.

Everyone has their own experience of the economy and money.

When John F. Kennedy ran for president in 1960, he was asked about his experience of the Great Depression. His answer surprised many voters.

The Kennedys, he said, were already wealthy in 1929. And over the next ten years, their fortune wasn’t wiped out – it actually grew. By 1939, the family had more servants and lived in a bigger house than it had at the start of the decade. It was only when he went to Harvard and read about the Depression that he realized how badly others had suffered.

Not all Americans, it turned out, had been in the same boat. Kennedy wanted to change that, which is partly how he convinced voters that he wasn’t just an out-of-touch elitist, but a worthy president. But it’s not only the rich and the poor who have contrasting experiences of economic life – we all do.

The son of an unemployed farmhand and the son of a successful Manhattan stockbroker don’t just come from different walks of life. They also learn profoundly different lessons about such things as risk and reward when it comes to money. But the same applies to equally well-off people depending on their individual life experiences.

For example, a wealthy individual who grew up during periods of high inflation will have a different financial worldview than a similarly wealthy person who’s only ever experienced stable prices. The resulting lessons of these different perspectives shape what we do with money.

We all like to think we know how the world works, but we usually only experience a small sliver of that reality. And that’s the first thing to understand when it comes to the psychology behind financial decisions: we know less than we’d like to think we do.

Personal experience drives financial decision-making.

When economists model financial behavior, they often rely on a convenient fiction. That is, rational individuals who make self-interested decisions that maximize their returns.

Reality, of course, is a bit messier than this neat idea. Consider, for example, the lottery. The average low-income household in the United States spends a few hundred dollars on lotto tickets every year. At the same time, around 40 percent of all households struggle to find $1,000 in an emergency. Unsurprisingly, this 40 percent is made up of the same low-income households who spend significant income on lottery tickets.

Is this behavior rational? Not at all. But it’s not illogical, either. If you’re living from one paycheck to the next, you’re unlikely to have enough money for essentials, let alone luxuries like vacations. Playing the lottery is a long shot, but it beats the alternative – not having any shot at getting the good stuff wealthier folks take for granted.

These kinds of irrational calls are more common than you might think.

A research study by several economists want to understand what American do with their money. They found several variables needed to be considered - what the economy was doing when the investors were young adults. Personal history, in other words, determines our attitude to risk. Like buying lotto tickets, this isn’t the kind of rationality found in economics textbooks, but it is intuitively logical.

If inflation was high between investors’ late teens and early twenties, for example, they were highly unlikely to invest in bonds later in life. If inflation was low during these formative years, by contrast, investors were happy to continue to put their money into bonds as they grew older – no matter if inflation grew along the way.

A similar pattern holds for stocks. If the stock market was doing well in early adulthood, investors went on to invest in it; if it was weak at the same age, they avoided it.

Assume you had been born in 1970. Between your teens and early twenties, the S&P 500 increased ten-fold. Anyone who put their money into companies listed in that stock made a killing. People born in 1950 had a very different experience of the market, which was pretty much dormant during this period in their lives. Consequently, decisions to invest or not didn’t change even when the market itself did, suggesting that real-world evidence failed to change gut decisions formed early on in life.

Personal experience drives financial decision-making.

Why are so many of us so bad at handling money? One answer is that it’s pretty new in the grand scheme of things.

The first currency was only issued around 600 BC. And that’s nothing compared to more complex economic concepts.

Take retirement as an example. Before the Second World War, most Americans worked until they died. Life expectancy was lower back then, of course – and even then, half of all men above the age of 65 still participated in the labor market in the 1940s.

Things started changing with the introduction of Social Security after World War II, but retirement remained an unattainable ideal for most American workers until the 1980s – the decade in which the average monthly Social Security check rose above $1,000, adjusted for inflation. Before that, only a privileged minority could afford to quit work in their mid-sixties.

That means that one of the most basic economic concepts we use in today’s world is less than two generations old. The 401(k) – the principle method of funding retirement – didn’t even exist until 1978, while the Roth IRA retirement scheme was only introduced in 1998.

Other key ideas and practices aren’t much older. Hedge funds only really took off a quarter of a century ago, and index funds are just 50 years old. Even consumer debt like mortgages, car loans, and credit cards – one of the primary drivers of economic growth in the United States – only became commonplace after the GI Bill made it easier for average Americans to borrow money in 1944.

If we’re bad at financial planning and decision-making, it’s not because we’re crazy – it’s because we’re lacking much experience.

Luck plays a bigger role in financial successes than you might think.

Robert Schiller, a famous economist and Nobel Prize recipient, was asked what he’d most like to know about investing that can’t be fully known. Schiller’s answer was the “exact role of luck in successful outcomes.”

Luck is a tricky topic. Few investors and entrepreneurs would deny that it plays a role in theory, but it’s hard to quantify the extent to which it’s responsible for one firm prospering – and another failing. We also tend to think that it’s rude to attribute others’ successes to blind chance. As a result, we often end up ignoring the role of luck when it comes to financial decision-making. That’s a mistake.

Recent research on personal finance found that the income of two siblings is more closely correlated than either height or weight. Put differently, if your brother is rich and tall, you’re more likely to be rich than you are to be tall.

It’s easy enough to explain this correlation. Siblings from the same household are likely to enjoy the same privileges and opportunities. Parents who send one child to a good school usually do the same for his brother. Find a pair of rich brothers, though, and you’ll find two people who don’t believe the study applies to their family.

That’s down to human psychology. We typically either underestimate or overestimate the role of luck in outcomes. If we do well, it’s because we worked hard; if we fail, it’s because we were unlucky. If others fail, though, we aren’t nearly as generous. In those cases, we don’t attribute failure to bad luck but to character flaws like laziness or shortsightedness.

Our culture, which is obsessed with success, isn’t much help here, unfortunately. Financial magazines do not celebrate brilliant investors who went broke because they were unlucky and the market took a sudden nosedive. They do celebrate second-rate or reckless investors who got lucky and made a fortune, however. Still don’t believe it to be true? Reference all the interviews with traders who bought into some of the latest crypto craze. More often than not, their entire net worth is in just one asset class. Even then, most investors and advisors would not consider cryptocurrency to be an asset class due to it’s extreme volatility and the inherent tax consequences with market gains.

That leaves us in a pickle. When it comes to money, we don’t just need to figure out what works and what doesn’t – we also need a way of building randomness into our models. We might not be able to fulfill Schiller’s dream and account for the “exact role” of chance, but – as we’ll see – we can get a handle on luck.

Focusing on broad patterns rather than specific cases can help you make better calls.

Bill Gates once quipped that “success is a lousy teacher.”

As Gates sees it, success tricks smart people into overlooking the role of luck, which in turn makes them think that they can’t lose. Paradoxically, that’s a pretty surefire way of ensuring that you do lose. I can attest to that as most military pilots like to think they have "The Right Stuff." In reality it took many of us that endured military flight training countless simulated emergencies (and some actual), to build our knowledge and technical savviness to complete risky maneuvers and combat missions.

So how should you build chance and luck into your financial behavior? Here’s what you shouldn’t do: obsess over the examples of specific individuals. When we study highly successful people, we usually end up picking outliers – the billionaires who’ve changed the way the world works – and that can lead us astray.

Take John D. Rockefeller, one of the most successful entrepreneurs in history. When he started building his petroleum industry, he faced a problem. The laws of the United States didn’t permit him to do what he wanted to do. His solution was simple – ignore them. His disregard for legal conventions was so great, in fact, that one judge said his business behaved “no better than a common thief.” (If you want a great read consider Titan by Ron Chernow)

Rockefeller’s success shapes the way we think about this behavior. Looking back, it’s easy to celebrate his vision and say that he refused to let outdated laws stand in the way of innovation. But what if he’d failed – would we still think that Rockefeller’s example is one we should follow? Probably not. At best, we’d see him as an unsuccessful criminal who taught us what not to do.

But when you get down to it, the difference between these two outcomes is luck. A couple of different verdicts here and there, or perhaps a change in the political climate, might have altered Rockefeller’s fortunes.

More importantly, good luck is all but impossible to emulate. Even if you mimic every career step of someone like Warren Buffett, you can’t ensure the dice will fall the same way for you as they did for him.

So here’s the alternative: stick to analyzing patterns of success and failure. The more common a pattern, the more likely that it’s applicable to your life and financial decisions. Study after study shows that people who control the structure of their days are happier with their work than those who don’t. Unlike the few cases of larger-than-life outliers, that’s a broad observation you can act on right now. In fact, we often recommend that clients consider working into retirement so long as they find purpose in what they do as it leads to greater longevity and quality of life.

Amassing a fortune is easier than keeping hold of it.

Many successful traders lost most, if not all, of their investment during The Great Depression.

Getting rich, it turns out, is sometimes a lot simpler than staying rich. It’s easy to see why people who are good at the former often struggle with the latter.

Making money is all about risk, optimism, and courage. Keeping money is an entirely different psychological ball game. It’s about the fear that everything you’ve made could be taken away. Staying rich also means being humble.

There are lots of stories of lost wealth, though their stories aren’t usually as tragic. Around 40 percent of all publicly listed companies lose their entire value over time. And the list of America’s richest people has a 20 percent turnover per decade, excluding cases of death and intra-family transfers.

So how do you keep what you already have? In a word, perseverance. The entrepreneurs who do best stick around for a long time without wiping out. What they all have in common is a little thing called fear. Some great advice I recall is when you’re scared of losing, you look at potential wins through a different lens. Few gains are large enough to justify risking losing everything you already have. And when you take that view, you’re much more likely to make better calls.

You can be wrong half the time and still make a fortune.

All great art collectors do the same thing – they buy vast quantities of art. Some acquisitions turn out to be great investments, especially if the collector holds on to them for a long time. The majority, however, are duds.

Patiently waiting is a strategy that applies to all investments. It’s often referred to as the long tail – the tendency of a small number of events to account for the majority of outcomes. There’s a lot of complicated math behind this principle, but it’s simple enough when you boil it down to the essentials. Basically, when you get a few things right, you can afford to get more things wrong. Failure is inevitable; what really matters is the nature your successes.

Too Long Didn’t Read “TLDR”

Financial decision-making is a lot messier in the real world than it is in economics textbooks. Lots of decisions – like buying lotto tickets when you’re broke – aren’t rational, but they do make sense in their own way.

When creating a financial plan with your advisor it is vital to understand that there will be some occasional losses that, more often than not, are offset by larger gains in your investments. Having a personal relationship with your financial advisor allows for them to understand what key emotions may be limiting your long-term goals. An amazing advisor will not only help you achieve those goals on a proper timeline, but will also help you retain what you have worked so hard to achieve, all the while limiting the tax consequences wherever possible.